Campylobacter in Dogs and Cats Understanding Zoonotic Risk and the Reptile Connection

A practical guide for pet owners on risk, hygiene and testing

Campylobacter is one of the most common causes of bacterial gastroenteritis in people in the UK. Most people associate it with food poisoning, particularly undercooked poultry, but fewer realise that Campylobacter can also be carried by animals, including dogs, cats and reptiles.

At ParasiteVet, our approach is grounded in evidence-based diagnostics and clear clinical interpretation. Understanding which Campylobacter species are involved, and how different pets carry different strains, allows owners to protect both animal and human health without unnecessary worry or treatment.

What is Campylobacter?

Campylobacter is a group of bacteria that live in the intestinal tract of many animals. Some species are capable of causing illness in people, while others may be carried without causing any obvious signs in the animal itself.

In humans, infection most commonly leads to diarrhoea, abdominal pain, fever and nausea. Most cases resolve without treatment, but illness can be more severe in young children, elderly adults, pregnant people and those with weakened immune systems.

Campylobacter in Dogs and Cats

Dogs and cats most commonly carry Campylobacter species such as Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli. These are the same species most frequently associated with food-borne illness in people.

Importantly, dogs and cats do not need to be visibly ill to carry Campylobacter. The bacteria can be detected in healthy animals, particularly puppies and kittens, or in pets that have recently experienced stress, dietary change, rehoming, or exposure to crowded environments such as kennels or rescue centres.

In some cases, Campylobacter may be associated with diarrhoea, especially in young animals. However, detection alone does not prove that it is the cause of illness, and results must always be interpreted alongside clinical signs and overall health.

Is Campylobacter from Pets a Risk to People?

Yes, but the risk is highly dependent on circumstances.

In the UK, most Campylobacter infections in people are linked to food rather than pets. That said, contact with animal faeces is a recognised route of exposure. Risk increases when a dog or cat has diarrhoea, when hand hygiene is poor after cleaning up stools or litter trays, or when vulnerable individuals live in the household.

Dogs and cats can act as bridging hosts, moving between outdoor environments and close contact with people. This means bacteria picked up outside can be brought into the home, onto hands, floors or soft furnishings. In most cases, simple hygiene measures are far more effective than medication at reducing risk.

Why Reptiles Are Different

Reptiles are biologically very different from dogs and cats. Their body temperature, gut environment and immune systems support a different range of bacteria.

This distinction is especially important when discussing Campylobacter. The Campylobacter species that genuinely colonises the reptile gut is not the same species commonly found in dogs, cats or poultry. Treating reptiles as if they carry the same Campylobacter as mammals risks misunderstanding both animal health and zoonotic risk.

The Reptile-Associated Species Campylobacter fetus subsp. testudinum

Scientific research has shown that reptiles are primarily associated with Campylobacter fetus subsp. testudinum. This bacterium is adapted to cold-blooded animals and can live in the reptile gastrointestinal tract without causing obvious illness.

Older literature sometimes refers to “reptile-associated Campylobacter fetus”, which can be confusing. Today, C. fetus subsp. testudinum is recognised as the reptile-adapted lineage and is genetically distinct from the Campylobacter species most often linked to food poisoning.

Why This Matters for Human Health

While many Campylobacter infections in people are mild and self-limiting, Campylobacter fetus behaves differently from the more familiar food-borne species. In humans, it is more often associated with invasive or systemic disease, particularly in older adults or those with compromised immune systems.

Serious illness remains uncommon, but this species is clinically important and deserves careful consideration in households that keep reptiles, especially where hygiene standards may be challenged or vulnerable individuals are present.

Diagnostics and Testing A Species-Specific Approach

Because not all Campylobacter species behave in the same way, how we test matters.

Many routine tests simply report that “Campylobacter” has been detected, without identifying which species is present. While this can be useful in some situations, it does not always allow accurate assessment of zoonotic risk or guide appropriate next steps.

At ParasiteVet, our diagnostic panels use species-specific real-time PCR, designed to reflect how Campylobacter behaves in different pets.

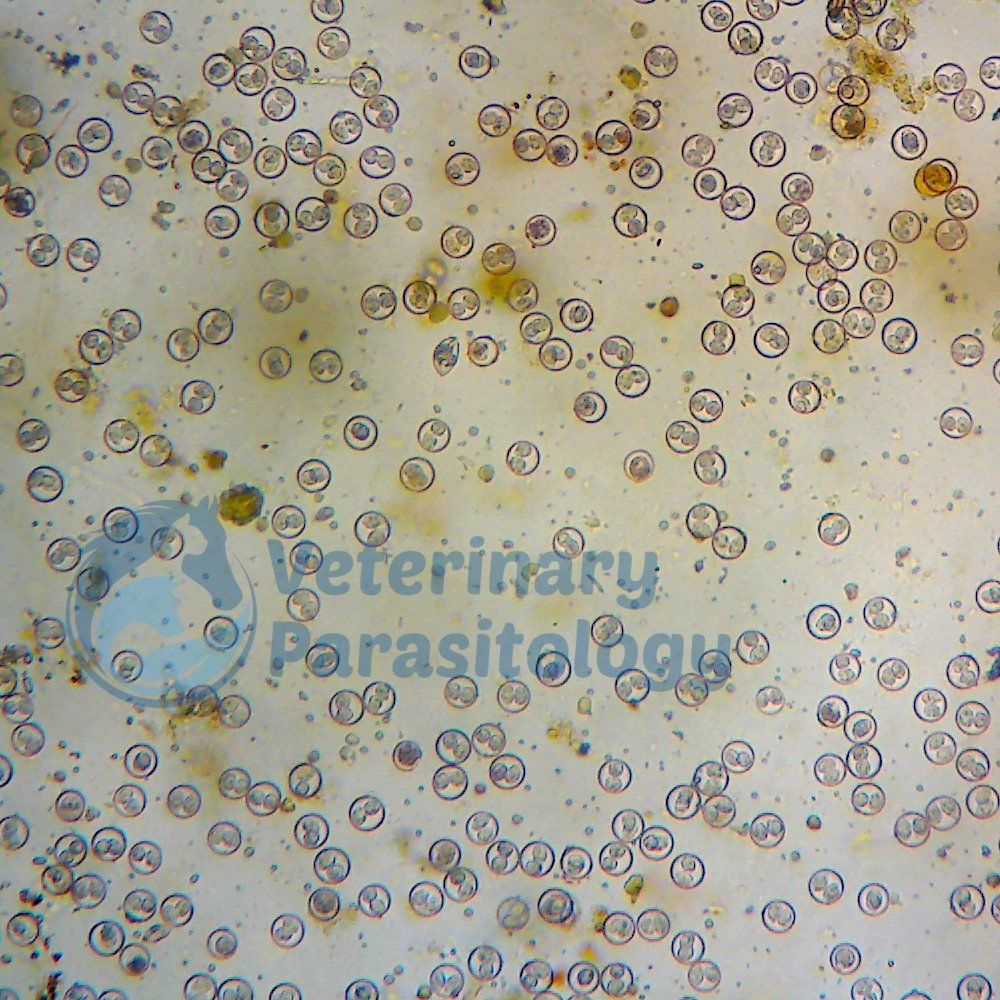

Reptile Testing

For reptiles, our PCR screening specifically targets Campylobacter fetus subsp. testudinum, the only Campylobacter species known to truly colonise the reptile gut. This avoids reporting non-specific results that may not be biologically relevant.

This targeted screening is included in:

Results are interpreted alongside microscopy findings and husbandry information, recognising that detection does not automatically indicate disease or the need for treatment.

Dog and Cat Testing

In dogs and cats, the Campylobacter species of greatest relevance to both animal health and zoonotic risk are Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli. Our dog and cat PCR screening therefore focuses specifically on these organisms.

This testing is included in:

This approach avoids vague “Campylobacter positive” results and provides information that is clinically meaningful for vets and owners.

Does a Positive Campylobacter Result Mean My Pet Needs Treatment?

Not necessarily.

Campylobacter can be detected in healthy animals, particularly dogs and reptiles. A positive result does not automatically mean Campylobacter is the cause of illness, that antibiotics are required, or that there is immediate danger to the household.

Treatment decisions should always be made by a veterinary surgeon, based on clinical signs, age, overall health and household risk factors. Unnecessary antibiotic use offers little benefit and contributes to antimicrobial resistance.

Practical Advice for Pet Owners

Simple hygiene measures are highly effective at reducing zoonotic risk. Washing hands thoroughly after handling pet faeces or cleaning enclosures, keeping reptiles and their equipment away from food preparation areas, and cleaning up faeces promptly all make a real difference.

Extra care is advisable if there are young children, elderly adults, pregnant people or immunocompromised individuals in the home. If a dog or cat has diarrhoea, faeces should be treated as potentially zoonotic until the problem has resolved, and veterinary advice should be sought if signs are severe or persistent.

The Take-Home Message

Campylobacter is not just a food-borne issue. Dogs, cats and reptiles can all play a role in zoonotic exposure, but not all Campylobacter species are the same.

Reptiles are uniquely associated with Campylobacter fetus subsp. testudinum, while dogs and cats most commonly carry Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli. Using diagnostic tests that reflect these differences allows for clearer interpretation, sensible hygiene advice and responsible, test-led decision making that protects both animal welfare and public health.

References

Public Health England. Campylobacter guidance and surveillance data.

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Campylobacteriosis annual reports.

World Health Organization. Campylobacter fact sheet.

Fitzgerald C. Campylobacter. Clinical Microbiology Reviews.

Wagenaar JA et al. Campylobacter in animals and public health relevance.

Gilbert MJ et al. Reptile-associated Campylobacter fetus subsp. testudinum.

Patrick ME et al. Reptiles as a source of Campylobacter infections.