Salmonella in Reptiles

To test or not to test

Reptiles are fascinating, unique companions. From colourful sliders to gentle bearded dragons and powerful boas, their popularity as pets has grown significantly over the past few decades. Along with that rise in interest has come an increased awareness of potential health risks, particularly the bacteria Salmonella.

For many years, Salmonella has been a concern in reptiles, not because it always makes the animal sick, but because of its potential to spread to people. Understanding this issue requires a look at history, science, and modern veterinary guidance.

A Historical Perspective: Sliders and the Turtle Ban

In the 1960s and 70s, small turtles, particularly red-eared sliders (Trachemys scripta elegans), were imported in huge numbers from the United States. Their small size, appealing appearance, and ease of transport made them extremely popular as children’s pets. Hatchlings often sold for just a few dollars at fairs, markets, and pet shops.

But this boom quickly led to a problem. Young children were frequently handling the turtles and sometimes even putting them in their mouths. Combined with poor hygiene awareness, this resulted in outbreaks of Salmonella infections in children. The link between turtles and Salmonella became clear, and by 1975 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) introduced a ban on the sale of turtles with a shell length under four inches.

The four-inch rule was chosen because larger turtles were thought to be less likely to be handled by very young children in a way that would pose the same risk. The law significantly reduced turtle-associated Salmonella cases in children, though small turtle sales did not disappear entirely, as illegal trade and unregulated imports continued.

Today, Trachemys species, including red-eared sliders, yellow-bellied sliders, and Cumberland sliders, remain some of the most common pet turtles worldwide. They continue to highlight the balance between keeping reptiles as beloved pets and managing potential zoonotic (animal-to-human) risks.

Salmonella in Reptiles: Carrier Status

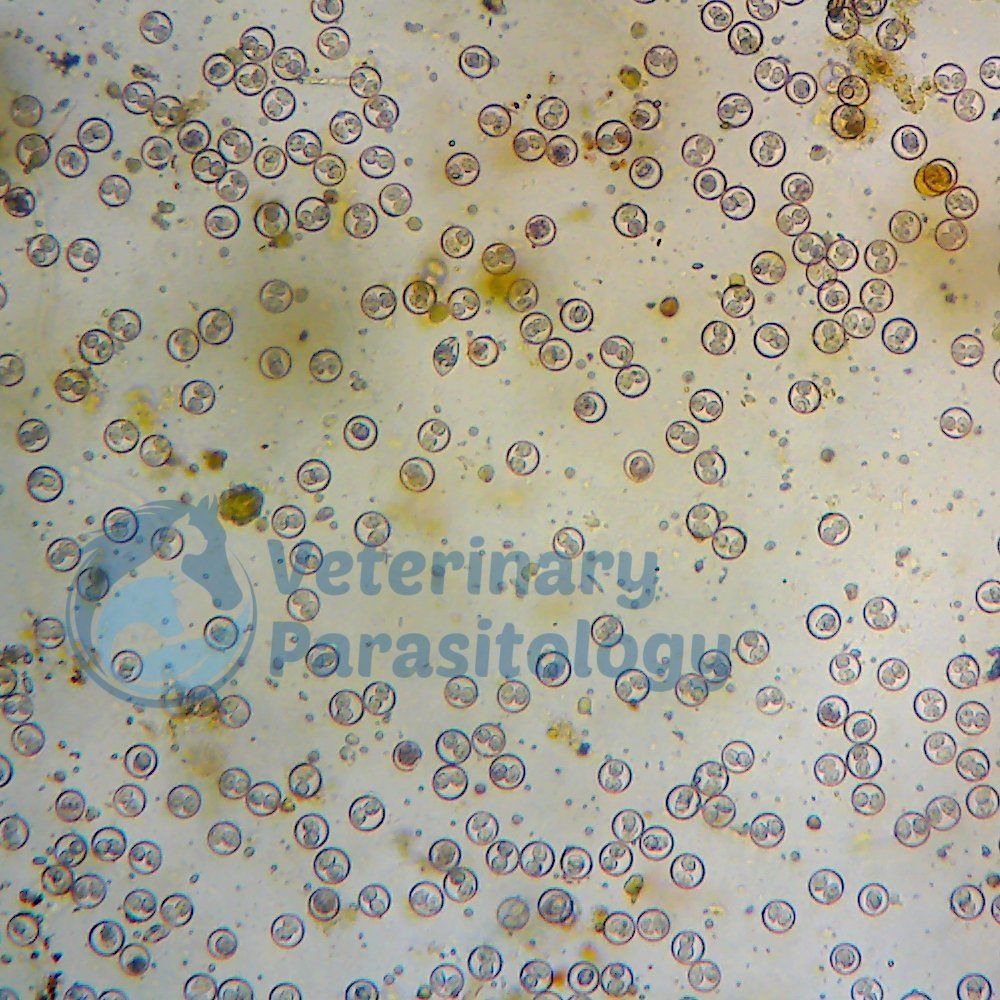

One of the most important things for owners to understand is that reptiles often carry Salmonella bacteria in their intestines without showing any signs of illness. In fact, for many reptiles, Salmonella is considered part of the “normal” gut flora.

This means a perfectly healthy-looking reptile can still shed bacteria in its faeces. Shedding may be constant or intermittent, and stressors such as transport, new environments, or illness can increase the likelihood of Salmonella being present.

For people, however, exposure can lead to salmonellosis, which causes diarrhoea, abdominal pain, fever, and in some cases more severe complications, especially in young children, the elderly, or anyone with a weakened immune system.

Importantly, although reptiles are usually symptom-free, there have been documented cases where reptiles themselves developed clinical illness from Salmonella infection. These are less common, but they do occur, especially if the reptile is stressed, immunocompromised, or kept in suboptimal conditions.

Should Owners Test Their Reptiles?

At ParasiteVet, we are often approached by reptile owners asking about testing their pets for Salmonella. Sometimes this is out of concern for children in the household, sometimes because a family member has been unwell, and other times simply for peace of mind.

The Association of Reptile and Amphibian Veterinarians (ARAV) advises that routine bacterial culture of reptile faeces is discouraged, mainly because Salmonella shedding is intermittent. A single negative result does not guarantee the reptile is “clear,” while a positive simply confirms what we already know — that reptiles commonly harbour Salmonella.

That being said, there are situations where testing may still be useful. In households with very young children, elderly relatives, or immunocompromised individuals, knowing if a reptile is actively shedding Salmonella can help families make more informed decisions about hygiene, risk, and management. Similarly, if a reptile shows clinical signs that could be linked to bacterial infection, targeted testing and culture may play a role in diagnosis and treatment.

So while routine screening of every reptile may not be recommended, selective testing in specific contexts can provide valuable information. The key is to discuss this with your vet and consider the individual circumstances of your household and your pet.

Responsible Ownership and Risk Management

Reptiles can absolutely be kept safely as pets, even in homes with children, provided good hygiene practices are in place. The goal is not to eliminate Salmonella, but to manage the risk of transmission.

Practical steps include:

- Wash hands thoroughly with soap and warm water after handling reptiles or cleaning their enclosures.

- Avoid cleaning reptile habitats, food bowls, or equipment in sinks used for human food preparation.

- Supervise children when handling reptiles and teach them good hygiene habits early on.

- Be cautious about keeping reptiles in households with infants, elderly individuals, or immunocompromised family members unless strict hygiene practices can be maintained.

The Bigger Picture: Why Education Matters

The story of sliders and the turtle ban is an important reminder of how Salmonella shaped reptile-keeping policies worldwide. But the real lesson is not to fear reptiles — it is to understand them.

Reptiles are not “dirty” or dangerous by nature. They are simply hosts to bacteria that can also affect humans. By recognising this and taking sensible precautions, owners can enjoy the companionship of their reptiles while protecting themselves and their families.

As vets, our responsibility is to support that balance. Testing may not always give the full picture, but open discussion, education, and individualised advice do. When owners feel informed and empowered, reptiles are more likely to receive the care they need, and risks to people are reduced.

Conclusion: Working Together for Healthy Pets and Families

Salmonella will always be part of the reptile world. The goal is not eradication, but management. With good hygiene, responsible ownership, and clear veterinary guidance, reptiles can continue to be safe, rewarding companions.

At ParasiteVet, we believe strongly in building trust with reptile owners. That means being honest about risks, offering clear information, and always remembering that we are on the same team. For some families, testing may provide reassurance or play a role in specific health concerns, while for others the focus will be purely on management. Both approaches can be valid when guided by a responsible vet-client conversation.

So if you own a reptile or are thinking about adding one to your family, take the time to learn, ask questions, and work closely with your vet. Together, we can protect the health of both your pets and your loved ones.